Webinar: Investigations Masterclass – The Human Element

Transcript for Investigations Masterclass – The Human Element

Giovanni Gallo: Hi, everybody. So, let’s jump in. We got a great panel for you today. Welcome, everybody, to our Investigations Masterclass with Matt Kelly, who will be talking about the human element today. I’m Giovanni Gallo, and together with Nick Gallo, we’re co-CEOs of Compliance Line, we provide essential compliance service to caring leaders for over 6 million employees worldwide, including hotline, case management, investigations, screening and monitoring, e-learning and things like that. We’re always looking for ways to help you make the world a safer workplace. And as part of that, we’re putting on this masterclass. Why don’t you introduce them, Nick?

Nick Gallo: Thanks, Gio. Yeah, we have a great group today. So, we have Matt Kelly as our host and moderator. We have Alejandra Almonte, Gabriel Imperato, and Scott LaVictor. So, Matt, why don’t you take it from here? Jump in and everyone, please participate. We want this to be as valuable for everyone attending as possible. And the best way to do that is to kind of turn this into a conversation. So, if you have questions, please raise your hand, drop those into the chat and we will integrate those into the discussion. So, I’ll let you take it from here, Matt.

Giovanni: Yeah, hold on. Sorry, Matt. Before you get started, just wanted to note to everybody that this course is SHRM approved and you’ll be getting an email with your credentials if you’re credentialed by SHRM, you’ll be able to account this for your continuing education units and that’ll be coming within the next day. I’ve had it, Matt.

Matt Kelly: All right. Well, thank you, everybody. And thank you Compliance Line for setting this up today. This is a great opportunity to talk about investigations. I know they are near and dear to compliance professionals’ hearts. I am just going to be your host. We have three great speakers lined up to walk us through some of the ins and outs of investigations and the best practices that they are trying to develop as they run their own investigations for clients that they deal with. So, I will just go through and do a quick round of introductions and then I’ll start firing away with my own questions. But as Gio and Nick said, as soon as you do have questions that come to mind, by all means, submit them. We will set aside some time for questions at the end, but if somebody asks something especially good and on point, we will try to work that into the conversation on the fly here. By just going in alphabetical order, so our first panelist that we have is Alejandra Almonte, who is a partner at the law firm Miller & Chevalier.

And she is the former general counsel for the America’s region for the Gate Group, which is one of the airline service businesses out there that you see when you look out the window, but when you’re waiting on the tarmac to take off. And in addition to that work, Alejandra has also been compliance monitor for several different engagements over the course of her career. So, a lot of good experience with investigations there. Gabriel Imperato, who is managing partner at Nelson Mullins, where he works primarily in the healthcare sector, either dealing with healthcare fraud issues or corporate conduct and corporate governance issues and compliance issues that come up with healthcare firms. He also served in-house as interim general counsel for the North Broward Hospital district down in Florida. And he is a longtime member and a board director for the Society of Corporate Compliance and Ethics Healthcare Compliance Association.

So, Gabriel, thank you for coming. And then lastly, we have Scott LaVictor who is cofounder of Arbor Insight, and that is a software firm that uses artificial intelligence to help clients of Arbor expedite the investigations process. And prior to his work at Arbor, Scott also was helping to run investigations at Whirlpool and various other organizations over the years. So, we have a lot of experience here. That is great news. I’m just going to dive in and again, I’ll just go in alphabetical order. I wanted to start with a very open-ended question, what do you see as the most difficult part of managing investigations and like what is it that companies seem to struggle with the most or not quite get right even if they know what they’re trying to do? But what is the choke point that you seem to encounter when you’re dealing with people? Alejandra, I’ll start with you and then Gabriel, and then Scott.

Alejandra Almonte: Sure. Thanks, Matt. It’s a pleasure to be here talking to you about this important topic today. So, as I thought through both looking at my in-house experience and external counsel experience, what emerged to me as the single most as you put it struggle in an investigation really boils down to managing client and other stakeholder expectations throughout the investigation process. And the way that I think through that, it’s really trying to strike that balance between conducting an independent, thorough, and objective investigation while at the same time balancing and acknowledging the interests that the business and other stakeholders in the company might have. And that really manifests itself in different ways. I think starting broadly as you’re scoping investigation, defining what the issues are going to be, how the process and investigation plan is going to develop, but then also in much more subtle ways.

And this really goes to the human element that I think we want to focus this conversation on. And it’s understanding investigations by their very nature are going to be disruptive. And there is that human element of employee morale that the company is going to want to protect and how to manage that human impact can be very challenging for counsel. And we tend to get focused on the legal and compliance aspects and lose sight of what sort of information the company needs to have in order to themselves internally be able to manage that softer side of an investigation.

Matt: All right. And, Gabriel, what do you see?

Gabriel Imperato: Well, a couple of things. Certainly what Alejandra mentioned. But sometimes I find that organization representatives are not quite sophisticated enough to understand what the fit is of an internal investigation in response to some compliance report. And sometimes it takes a little bit of explaining how that process of investigating and responding to reports of non-compliant activity plays into not only important aspects of governance of the organization, but managing risk and liability. The other thing that often happens a lot that I hear is, you know, you might start on an investigation and, you know, obviously your client is the organization, not necessarily the C-suite representatives of the organization, but of course, they’re always wanting to know, when are you going to be done with the investigation, you know? And the honest answer to that is I’m going to be done when I’m done, but, you know, that’s not usually an acceptable answer for those managers.

So, you have to manage those expectations. And I think the other thing that I would put in place, you know, internal investigations can come in many different forms and it’s actually if you’re going to do an effective internal investigation, that’s actually hard work and you need to be tenacious and you need to sometimes run down factual matters to their end because it never ceases to amaze me that I usually find out something I didn’t expect when I start every investigation. And I think it’s important to an organization to get down to that granular level sometimes despite what the representatives of the organization may like you to do because of other stakeholder interests.

Matt: And then Scott, what do you think?

Scott LaVictor: Well, thanks, Matt. You know, looking at it from the human element and from the investigator perspective, I think one of the biggest challenges is managing that blend of what I would’ve called in my previous career human intelligence, the interviews, right? And data collection, whether it be open source intelligence, hotline reports, HR, finance, marketing data and managing those inputs and gaining advantage from those inputs within the time and resource constraints that you’re faced with. So, that’s the biggest one. I think secondarily, at least in the context of our discussion day, but a big one is understanding, appreciating, and addressing the personal implicit and explicit biases investigator brings into the room. You mentioned, I think, Alejandra, that investigations are by nature disruptive. I think obviously by nature, investigators need to appreciate that, you know, for example, I’m a white cis-gendered male and what impacts that has on both the interview and the investigative process.

Matt: All right. Now, let me follow up then just listening to what you all had said. Originally, my follow up was going to be, why are companies not getting it right? Whatever it the most difficult thing was. But really what I’m hearing more is, like, how can investigators overcome sort of a natural hesitation around the organization? And by definition, if there’s an investigation happening, something probably isn’t going right at the very least, there’s confusion about what is or isn’t happening. And then Alejandra, to your point, it’s disruptive. And a lot of people are going to want to not have you there or wonder when will you go away or what is it that they can do to make this all end? So, I guess maybe my follow up isn’t why are companies not getting it right, but more, how can an investigator at the very start sort of find the natural allies or strike the right tone to explain to everybody, this is why I’m here. I am not the enemy. Let’s try and make this as pain-free as possible. Like, you know, do you say that you, do you want to be proud of the audit committee if they’re leading this investigation or your general counsel, or, you know, who are your go-to is to say, “I want to make sure that these people are aligned with what I’m trying to do?” I don’t know, Alejandra, I’ll start with you again.

Alejandra: Sure. I think it’s one, identifying the factors that we’ve all talked about, right? So, identifying those human elements in the investigation process and actually really directly speaking to them at the very beginning. So, you present your investigation plan, don’t hit the ground running, right? Sit down with who your client is. Your main contact is and have a conversation with them about what exactly this process is going to look like, what you anticipate at that time. And I agree, Gabriel, there are always things that come up, right? So, what the investigation means, what the investigation doesn’t mean, what you need from them from a resourcing and cooperation standpoint, what cadence of communication you’re going to have with them. And I think that that is a critical point that we very often gloss over, right? It’s, we’re going to start, we’re going to send a bunch of document requests and tell you who we need to talk to.

And then there’s really kind of a black box on when those next points of communication are going to be, I think establishing a natural cadence that’s going to put you in a position to ensure the client that you’re trying to avoid surprises for them and make them a natural part of the process always of course, without jeopardizing that independence that is important. And that’s something that I’ve seen a lot of clients struggle to understand, particularly, as you start talking to other employees throughout the organization, what does it really mean that you’re conducting an independent investigation? How does that impact me as an employee? But yeah, I think to synthesize it, it’s really identifying who the stakeholders are, what their concerns are going to be at the very beginning, and speaking to those concerns very directly. And then again, just establishing that cadence of keeping information flowing.

Matt: All right. Gabriel, what do you think in response to that? Like how do you sort of walk through those points that Alejandra was mentioning when you’re going to lead an investigation?

Gabriel: Well, it actually makes me think of something that occurred a couple of weeks ago as I commenced an investigation. My contact at the organization, you know, was not very familiar with the process. And I found myself at one point advising the contact who was like the executive director of a very large physician group. I told her, “Listen, your executive committee is going to be asking these questions very soon. So, what I think we should do is set up a meeting with that committee and we’ll address those questions before they even ask them,” because you just know from experience that that’s going to come up. The other thing that I thought of, you know, I’m in the healthcare industry. You may or may not realize that in the healthcare industry, they’re experiencing perhaps 600 to 700 new whistleblower False Claims Act cases a year in the industry, which makes the risk of not conducting effective internal investigations of reports of non-compliant activity a very acute risk. That dynamic enables me to explain to healthcare organization representatives, why it’s important to respond, you know, to these reports of non-compliant activity with an effective internal investigation as a means to manage that risk before it becomes an external risk. And that makes it a little bit easier in the sort of dynamic and with the stakeholders, because they do understand that risk.

Matt: And then Scott, what do you think?

Scott: Well, I certainly agree with that. I had on my list, you know, managing relationships with gatekeepers. As we all know, those gatekeepers of the business process, focused folks. This is a disruption for them and managing their expectations through regular communication, giving them examples of how you expect processes to unfold and how they’ve unfolded in some similar circumstances as certainly a key to making sure that the process unfolds as you would like. I think also empathy. I think I start with that in every relationship and every investigative process, letting that person know that you appreciate that they have another job to do that. This is disruptive, whether that be somebody in the C-suite or a staff member that you are interviewing. Looking at the process from their perspective and giving voice to the challenges, concerns and perhaps suspicions they have, so that you put a voice to it, address it, and then you’re able to move on.

Matt: You know, Gabriel and Alejandra, Scott mentioned that, that was interesting. Maybe give them examples of here’s typically how I have seen these investigations go before. Here’s what you should expect is that a, I guess, a best practice or a tip that you would recommend for investigation offering some of the potential targets or stakeholders. Here’s a sample of what you’re probably going to see as we do this. Is that a good idea?

Alejandra: Absolutely. I do think, and I really appreciate, Scott, your comment about empathy. I think that goes a very, very long way. All three of us, interestingly, have in-house experience. And I think that that’s something that I certainly appreciated for my external counsel is, you know, it was the first time we were seeing certain things within the company and there’s comfort in knowing that the person who’s advising you and leading you through this process has seen it all before, right? Misery loves company. And I think that certainly comes to bear in these situations. And also, you know, one thing I want to add, Gabriel, that you said that struck me too, is going to this issue of communication, which I think is another way of putting the business at ease is trying to understand what the cadence of the business is and where your client is going to be asked for information and making sure that you anticipate that so that you can get them the relevant information for the questions you know they’re going to have to answer in the information they’re going to have to provide, right? It really is demonstrating that you care, Scott, to your point about their function and their role, and you’re there to support them as much as you are helping them get to the right answer through the investigation.

Gabriel: Yeah, I would add to that, Matt, going to the empathy issue, knowing the cadence of the business, trying to fit into the fabric of the business, what your objectives are in the investigation. So, two things sort of come to mind. One, I’m always pretty flexible on how I conduct an investigation, how I accommodate the schedules of individuals I might want to interview, accommodate the production of documents that may be important. I’m not impatient about that sort of stuff.

I find that it’s important to be flexible and to have some agility in doing that. I think the other aspect is, I’m always, you know, mindful of the compliance and governance function overall for the organization. And because of that, I don’t want to compromise the organization’s future effectiveness to respond to non-compliant activity by being a jerk and conducting this internal investigation with the employees of the organization. I don’t do the organization any good by conducting an internal investigation in a way that turns off the constituents’ employees to the next investigation that has to take place. And I’m always really sensitive to that. And I find that it’s not hard to accommodate that concern, and still, you know, conduct an effective internal investigation.

Matt: That is an excellent point. Gabriel, let me stick with you, because I’d want to move to some more specific questions, maybe around, say, scoping and investigation, and just give us a sense of how you would try to get a precise scope of a matter when most of the time you’ll have a good idea of it’s pretty much this sort of a thing. We already have this whistleblower allegation that’s 70% of the way there, but you still need to figure out the exact scope and get from 70% to 100%. So, how do you go about doing that?

Gabriel: Well, first of all, I’m usually conducting an internal investigation as outside counsel directing agents, which may be internal to the organization or could be external as well in assisting with the conduct of the investigation. So, that becomes like a law firm engagement. And in my engagement documents, I will describe an initial scope of the investigation in writing. And that’s not only important for law firm client relations. I think it’s important for conducting an internal investigation because your initial scope is going to guide your efforts going down the road. Now, that isn’t to say that you might not expand that scope at a later time as you learn other things, but let’s say, for example, you stumble onto an issue that is completely collateral to the scope of your original scope. Well, I may not be spending time on that collateral issue.

I got it noted. Maybe somebody else will pick up that issue, but I’m staying on my original scope track. And I think it just is important to interject the discipline in your investigation. The other thing about scope that I think is important is you will establish by a preponderance of evidence as you’re going through your investigation, certain facts, and once you get to that threshold, I kind of put those facts on a shelf. I don’t, you know, eliminate them. I may come back to them later, but now I’m starting to tailor the investigation and moving to other facts that are going to be important to build the final report of information that I gathered.

Matt: All right. Alejandra, give us some thoughts of yours about scoping. And I was particularly intrigued, like we said, at the intro, you’ve done compliance monitorships several times. We don’t need to necessarily say which ones, but usually, these are big honking messes that a board is trying to figure out. You come in, you have a rough sense of exactly how big the mess is, but you still have to hone it down to a precise measurement of what you’re doing. How do you try and approach those kinds of things?

Alejandra: It’s pretty similar to what Gabriel said, right? I mean, you scope it as the allegation comes in to understand what the facts that have been alleged are and what that means, right? So, what are the legal questions that those allegations raised? What are the compliance implications that the allegations raised? Who’s the subject of the allegation, right? That’s going to change the…it’s almost a risk assessment, right? At the initial phase of the investigation that continues throughout, you know, and it’s understanding where the facts that you’re hearing through interviews and through documentation are taking you and being, Gabriel, to use word very disciplined as to where you are going based on those facts and those allegations. Collateral issues will arise, and it’s very easy to go down those rabbit holes. But it’s more effective for the investigation and for the wellbeing of the company to flag those, obviously raise them when you identify them to the client so that they can determine whether or not a separate investigation is necessary, whether the scope of your investigation is going to expand in some way, but very important that those parameters be well-defined.

And again, that constant interaction of communication with the client is very important because, at one point, the investigation will have to come to an end. And I think that’s just as challenging as defining the initial scope is knowing when you’ve reached the outer layers of what you’ve scoped up as your issues and of your investigation is so that you’re primed to give your findings, to deliver your findings to your client with recommendations that will help them make the decisions that they need to make from a legal perspective.

Matt: Okay. Scott, what do you think?

Scott: You know, I’m going to jump ahead to some comments I was going to share later, but in agreement with Alejandra and Gabe, if I want to add, you know, my background is, as you might know, is a large part of it was in the intelligence business. And there, we described the process much like, you know, putting together a puzzle without the picture on the box, right? So, I’m a bit more comfortable with some gray areas in terms of scope. I tend to approach it like an all-source investigator. So, in the intelligence world, an all-source analyst is somebody who brings together other and client destined information. As an all-source investigator, I like to consider all of the available data analytics documents, people to interview, open-source intelligence, and then begin to scope around that, understanding of course that, you know, context, as I often say, context is king, context is queen, and the amount of information I can gather upfront to help validate that starting point and follow not necessarily focus overfit on interviews but, in fact, take a look back and say, “What does the data show me? What is the initial report show me as to where this path might take me and build out from the most valid or reliable information that context over time.” You can do that and still maintain some level of discipline and make some progress there.

Matt: Okay. And I wanted to ask a few questions about managing a whole investigation program as well. And I’d like to pick up an idea that a lot of compliance programs, in fact, all of compliance programs should have several elements that can help with investigations, and maybe how somebody who’s listening here, how you could leverage some parts of your compliance program to help with investigation work, namely, the intake system for internal reports, and then any case management system you might have in place after the report has entered your system and it’s floating around. So, maybe if we could start with talking about the intake system for internal reports, how could that be tailored or leveraged to extract as much useful information at the beginning so that you can help to set the path of your investigation and the scope from the start rather than trying to figure that out. Alejandra, what do you think first, and then I’ll ask Gabriel and Scott after?

Alejandra: Sure. I think it’s identifying again, those criteria that are going to help you when you first see the allegation come in, assess the risk and the impact of the allegations, right? So, questions of what happened. And I think it’s important to have somewhat of an open-ended approach so that the person who’s making the allegation can give you with reasonable detail, what it is that happened, who was involved, who has knowledge, when did it happen, where did it happen? How do you know, right? How did this issue come to you? That will help you understand again, what is the seriousness of it. And, you know, when I think about it, what does that mean? What does the seriousness of the allegation? To me, it really is, what is the worst-case scenario?

What is the worst thing that can come out of this allegation? Is it criminal conduct or is it a more minor code of conduct violation as we understand it when it comes in? And that will allow me then, Matt, to your point is to see what other resources I need available to me, either internal to my organization or external to help me respond to the degree of risk that this allegation presents to my organization, both from a subject matter expert, I need to have the right resources available to help me unpack it. If it’s accounting issues. I need to have someone who’s going to help me effectively investigate that issue. Again, to more challenging criminal conduct, where you’re likely going to be coming to an external counsel to help you through that.

Matt: Gabriel, what do you think?

Gabriel: Well, it makes me think of the intake process that I was able to observe when I was at the North Broward Hospital District. Their compliance department had a pretty good form that would be completed upon a report on their hotline. You know, going to the concept of the more information upfront, the better, it might be nice to maybe ask at that stage the reporter of what they think they’re reporting. You know, I often ask that question in my interviews especially of a reporter of non-compliant activity. “Okay. I see what you’ve reported, what about this, do you think is a compliance issue? Why are you reporting it? What do you think is the problem?” And the other initial issue I want to explore is what the source of the reporter’s information is, what kind of information do they have access to both in the organization and outside your organization to, you know, color the scope and credibility of their report because that’s, you know, my experience is that the reporters, especially in the healthcare industry, which is, you know, a regulatory complicated industry, reporters usually have about 40% of the full picture and not the whole picture.

So, I always want to get a sense, what non-compliant activities that you think your reporting, and what is your sources of information about what the activity is that you’re basing your report on? The more of that you can get upfront on the intake process or even get an inkling of is going to help with your scope and your work plan going forward.

Matt: Sure. And Scott, what’s your sense of how to design a smart intake plan to be able to ameliorate or amplify some of these questions that come up?

Scott: Yeah. So, as you might imagine, this is near and dear to my heart and goes to the origin story of Arbor Insight. But, you know, the intake…that’s where the investigation begins, right? Somebody is providing information to a person, a system that is asking relevant questions. That’s an interview, that’s the beginning of the process. And I would say that, you know, for too long, it’s been treated as a commodity, a check the box part of the technology suite or the process. Maybe we’ll just throw a phone hotline out there, a voicemail extension, but it can easily become a value add that first contact that augmenting the investigative workforce, facilitating the triaged, inappropriate scoping and investigation if done right.

And for me that, you know, what is done right mean? And that means meeting the staff where they are. Understanding how workplace communication preferences changes and has changed over time and embracing that, and appreciating that as a primary driver for how that intake process occurs. I think if you don’t do that, you know, all the money you’ve spent on training and awareness programs and on, you know, investigator or legal resources is thrown out the door because you’re creating a point of friction in the reporting process. And that funnel now is becoming more and more narrow because people who have been trained or incentivized through culture, through policy, through regulation to speak up are now being faced with an intake mechanism that just doesn’t fit with how they want to communicate with the world, especially in the workplace.

So, going back to what Gabe said earlier, you know, it’s, you’re going to have to come back to these folks and ask for their help later. So, we want to give them a great user experience. You know, we call them, you know, our approach as a human as a sensor approach. And the way we do that, that human as a sensor approach and achieve reliable, actionable, relevant data, is we guide them through a process. So, whether you’re an investigator in front of them, or you’re using an advanced form of a machine intelligence, you want to guide folks through an expert-driven interview and collect that critical contextual information that is so valuable to your process. Bottom line is, you know, what I like to say, and that Arbor Insight, it’s not just about what users want to say, but it’s about what you need to know. And so, that 40%, you need to increase that to 60, 80, 90, you get that, you know, towards that 100% level. And if you need to do that in an impersonal way, you need to have the resources to accomplish that and especially in today’s workplace environment.

Matt: Now, let me ask you, yeah.

Gabriel: Matt, if I could, running on that, it’s also very important, what Scott had pointed out to the effectiveness of an organization’s compliance program and managing the risk of these reports of non-compliant activity becoming reported externally, it’s important that your constituents know that if they report something that the organization is going to take it seriously, is going to run down the report to whatever ends it reaches. And as you do that and build confidence in your workforce that if they do report something, it will be addressed, then the organization is going to learn of noncompliant activity in the way that they want to learn about it so that they can address it and more better manage the risk of that activity.

Scott: Exactly. As the DOJ said, sorry, Matt, just, you know, as the DOJ said, in their updated guidance that we’ve all appreciated by now, our staff members aware and comfortable with that intake mechanism, and that needs to be a key driver.

Matt: So, Gabriel, let me pick up on something you had said, and the human element of this is the theme here. What are some of your go-to moves or best practices in dealing with the actual reporter? For example, I have heard, I don’t know if this is true, but I’ve heard that a reporter will try and submit a claim twice. And if you have not taken action or somehow communicated back to them, we heard you, and we’re going to look into it. If you haven’t heard it by the second time they raise it, they’re going to say, “Peace out. I’m calling the audit firm or the regulator or the police or somebody else.” But what are some of your ways to make sure you keep the reporter close as much as you can so that they do feel like, all right, I’m dealing with the right people? What would you recommend?

Gabriel: Well, I think the best way I can answer that is by a short example of the situation a couple of years ago. A report was received by the organization’s hotline by a financial analyst type in the organization that he was asked to cut a check for medical staff physicians of the client’s hospital. And this particular individual had come from an organization who learned the hard way about cutting checks to medical staff physicians at their hospitals. And the check request was for an LLC and he just did some basic research on the secretary of state’s website and learned that the LLC members were these two physicians at the hospital. So, he reported this on the corporate responsibility hotline and said that, you know, that seemed unusual to him. And he thought that that was probably an improper payment.

So, we began to investigate the matter. And as we were doing that, we learned that this particular individual was making comments to colleagues that he worked with, well, where I came from, you wouldn’t cut a check to a physician unless five people signed off on it. I’m going to be interested to see how this organization deals with this issue. When I heard that, I became concerned about managing the whistleblower risk in this situation, and I thought it was important to make sure that that particular reporter knew that the organization was responding to his report in a meaningful way. Shortly after I concluded that, my partner raised a question in the context of our investigation, which required some CPA expertise to answer, and I knew the reporter was a CPA, and I recommend to my partner.

We’ll go back to him and ask that question because whether he can answer it or not is irrelevant, he’ll know by virtue of the question that we were doing our due diligence in response to his report. And, you know, that was one way to kind of communicate that, you know, we’re not ignoring what you’re doing. We’re definitely on this. Just last week, I had a similar situation where I read some early interviews, and clearly there were characteristics that I identify as a whistleblower in the mixed characteristic. And I recommended to the client that we need to probably have a little bit of direct communication with the reporter about our “progress” in the investigation.

Matt: Okay. Alejandra, what would you recommend, or what are some of your practices to keep the internal reporter close and make sure that they feel heard or seen?

Alejandra: Sure. And I think I’ll answer your question in two parts, Matt. So, first directly, what you do with an actual reporter timeliness is key and the DOJ highlights that, right? I mean, one of the data points that companies should be tracking is how quickly are you responding to allegations? What we hear in compliance assessments regularly when we do focus groups and talk to employees who interact with these reporting channels, much of it is how quickly they hear back from HR or compliance or legal when they file a report, and organizations can very quickly lose credibility if an allegation is made in too much time lapses before you even acknowledge the fact that this report has come in. I think important to acknowledge it from someone at the company, not just through an automated system that says, “Thank you, your complaint has been received.” Right?

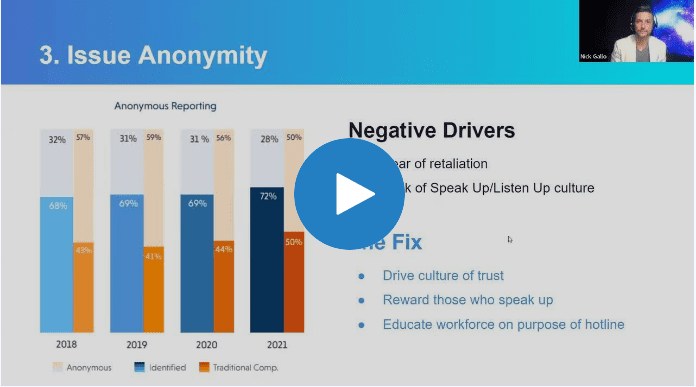

Second, you know, once the report has been taken in and you’ve identified who it is, and we haven’t talked about anonymous reporting, right? So, assuming you’re able to actually engage with the complainant, what we see clients very often struggle with is what can you communicate to the person who’s filed the report as the investigation progresses? Because this person wants to know they’ve been heard very often measures that the company takes. Won’t always be visible, right? Easy to say when the person that’s been accused of wrongdoing is suspended, the person who’s made the complaint presumably sees some of that. But it’s not always that cut and dry. So, you know, encourage clients to think through. And this is a bit of a case by case basis of what type of information is appropriate to let the complainant know that they’ve been heard and that the issues are being addressed.

And when I said I’d respond to your question in two parts, the other piece is that I really think communication with a complainant starts even before a complaint is made. And what I mean by that is that as a company, you’re constantly, whether you know it or not, messaging to your employees how credibly you will take allegations that are made in good faith. And that can be done in several ways, right? One is how actively are you socializing your reporting channels? How aggressive is your campaign that you welcome complaints and that, you know, your employees have an obligation to elevate wrongdoing. In trainings, right? It’s not enough to end the training with, “Here’s your reporting hotline.” You have an obligation to report, but make sure that you’re baking in lessons learned so that employees in an anonymized fashion can see that, wow, okay, the company has addressed difficult situations appropriately in the past. So, that’s what I mean when you’re starting to generate that trust, it happens even before somebody makes that first call.

Matt: Scott, any other suggestions and best practices for internal reporters?

Scott: No, I think Gabe and Alejandra really addressed it quite well. I think messaging outcomes. So, setting expectations both as a company and individually, letting folks know that they’ve been heard, recognizing that in that communication with the individual, who’s made that very difficult decision to speak up that less than 10% of that communication is really the words you use. And it’s really about the tone and style of that communication, letting them know that they’ve been heard, managing expectations upfront as Alejandra and Gabe said, I think is the best way to handle that.

Matt: We already have a bunch of questions coming in, so I’m just going to jump in and take one or two of them now. Here’s everybody’s favorite subject, if you’re a compliance officer, how do you best approach a situation where compliance issues have HR tentacles? So, now we’re onto compliance and HR and how they play nicely sandbox. Do you go ahead and wrap those issues into your scope and partner up with the HR function? Or what about when the employee says they have raised issues to HR before and nothing was done thereby making HR part of the complaint? How do you best approach something like this? I don’t know, Alejandra and Gabriel, which one of you want us to draw the short straw to talk about compliance and HR playing nice. What do you think? Gabriel, I haven’t had you talked for a bit yet.

Gabriel: All right. Well, yeah, I’ve had that experience numerous times where I’d have to interface with the HR. You know, sometimes it’s in a context where HR has received a report of non-compliant activity that’s very important to the company, but hasn’t recognized it as such and has dealt…was it really as just in the silo of an HR issue? And I’m thinking about a particular case a couple of years ago where the issue was very important. We had to move it out of the HR and investigate it as a non-compliant activity matter. The other interface with HR can be with their practices for doing exit interviews. And when they decide to take action with, you know, maybe key reporters or people with important information to the scope of the investigation that you’re doing. And sometimes that just boils down to trying to make sure that there’s a commitment to cooperate even if there’s an adverse HR like a separate situation and having the ability to maybe access those individuals for information that pole in the scope of your investigation.

Matt: Alejandra, what’s your thoughts and advice on this issue?

Alejandra: Sure. I think that the last part of your question starting there and then I’ll work backwards is, where there is an allegation that this was raised to HR before and the complainant feels it wasn’t properly addressed, that comes into the scope of the investigation and that if that is true, that’s one potential signaling of the effectiveness of that part of the compliance program that needs to be elevated to ultimately the client and helps assess at the end of the day what the risk is, if these allegations, right? If this is something that’s been reported to the company for some time, that very well could change the risk calculation of the consequences of this allegation, right? Again, going back to thinking of in the worst-case scenario, right? What’s the worst possible outcome that would factor in that way. If it’s just an HR issue that arises as you’re conducting an investigation, that’s, you know, that horrible. It depends. I’ve had recent experience actually in an investigation where an HR issue did come up that was tangentially related to what we were investigating. And, you know, to the extent that it informed our investigation, we folded that component of it in but did advise our client to simultaneously seek employment counsel on how to address those elements of what we would come to our attention, but that fell outside the scope of our investigation.

Matt: I should add, even as we were talking now, we got a bonus question from the audience about HR. And Gabriel, maybe I’ll pivot back to you here for this. How do you have HR step aside and allow compliance to take over the investigation? Because you had mentioned that you’d had an issue where occasionally compliance would need to step in. Okay. How do you make sure that ability to see that I should step in and HR should step out? How do you make sure that you have that visibility and then, you know, how do you diplomatically tell HR, “There’s the door, please step through it?”

Gabriel: Well, first of all, you would hope that the organization had developed their compliance program to the point where management or the compliance officer or maybe the compliance committee could effectively accomplish that objective just because they have mature leaders and they understand the difference between HR and compliance. But sometimes, I’ve been put in the position where I have to be the messenger for that particular message and advise the client that, you know, you have to move these constituencies aside and let this process play out and get HR to step down.

Matt: Scott, do you have any thoughts about either dealing with HR or actually somebody else asked a related question about concurrent investigations that might be happening on the same issue such as maybe your outside audit firm is suddenly looking into financial misconduct as well. If they find out about it, they are duty-bound to look into it too. And now you’ve got two investigations that might be bumping heads, but, you know, do you have any thoughts about how to make sure the bumping and buffeting that goes on there, like how to make sure that happens as well as possible?

Scott: Well, I think, you know, we want to first and foremost make sure to speak it doesn’t become a turf issue, right? So, you want to make sure that you collaborate and cooperate and communicate, three Cs that just came to mind. But, you know, you’re going to end up looking at some of the same data and you should be, you’re going to end up interviewing some of the same people and you may well be. And communicating as to why those dual interviews, those dual investigations are occurring is going to be key to making sure that it is not overly disruptive and doesn’t negatively impact either organizations or entities, investigative process, and just briefly to HR, you know, that’s a bit of a sticky wicket, right? And I look at it as a judgment call. Is there something substantial that needs to become part of the investigation with regard to HR activities? And if not, then we look to previously established alliances within HR to navigate that area. And if need be, you know, obviously get heads of HR, head of compliance, head of, you know, legal counsel, involved to help figure out from a risk-focused perspective, where do you want your activities to hit?

Matt: Yeah. I should tell everybody. I can clearly remember the first-panel discussion I led about compliance and HR, it was in 2008, 12 years later. We are still here. I look forward to leading another panel on that in 2035. But, Alejandra, let me also ask you, what about this idea of dual investigations that you’re just one of several that might be floating around. Do you have any advice on how to handle that sort of tension, for lack of a better word?

Alejandra: I do. You know, when I started talking about the biggest challenges that we face, I talked about managing not just client expectations, but also stakeholder expectations. External auditors are one of those external stakeholders that often have to be managed in our investigations. And, you know, our practice has been to bring the external audit to the table and really explain to them what it is we’re investigating, the scope of our investigation and offer, again, a cadence of communication where we are appropriately, right? Sharing information of where our investigation is, where it’s going and what we are finding. And that has been successful in some circumstances, particularly, when there’s a trusting relationship, not inappropriately trusting of course, but between external audit and gatekeepers within the company. And we’ve seen external auditors sometimes, you know, back down a bit to let our investigations progress with a force of promise that there will be appropriate touchpoints with external auditors, but it’s not an easy dance.

It’s certainly more of an art than a science and is influenced by a whole host of factors. If I can just really quickly to Matt on the HR and how you get HR to step down, when necessary, one of the fallbacks you said, how can you do that diplomatically? One of the fallbacks that I always go to is just the need for an independent investigation. And that way it’s nobody, in particular, is being cast aside. But for the investigation to truly be independent and objective, and for employees to feel that they can come to this process without any risk of retaliation or any of the other negative repercussions and to speak freely, it’s advisable that no one from the company actively participate directly in the investigation, you know, other than how we might direct as appropriate. That’s just a diplomatic talking point.

Matt: Gabriel, I’ll give you this next question from the audience, somebody just asking, do you have any tips for writing a report at the end of an investigation? And I’ll tack on my own extra question here, should a report also include recommendations on possible discipline? What do you think?

Gabriel: Well, first of all, I usually do not recommend preparing a written report at the end of an investigation and advise the client that I would be more inclined to report findings orally before I put pen to paper. Sometimes the clients insist for a lot of collateral reasons and a written report. And, you know, I’m happy to prepare a written report, but I usually tell the client you’re going to want me to put written findings on the letterhead of my law firm, which means I’m going to talk inside the support for that report. And it’s comprehensive ways I can before I put pen to paper on my law firm’s letterhead and that’s going to cost quite a bit of money. So, if you really need a written report, we’re happy to do it.

I just recommend an oral report in most situations, not that I don’t have all the basis for that report in my own file, you know, in the law firms file, but that’s usually the way I approach it. And in many situations, the oral report is adequate. I probably would not venture into a recommendation for discipline for particular individuals. I think that’s uniquely something for the compliant to decide, you know, I’m in the business of law. You know, that’s probably for some other party to sort of recommend or decide either the client or some other type of consultant. That would be something I would avoid weighing in on.

Matt: Okay. Scott, what do you think about report writing and best practices there and then Alejandra after that?

Scott: Yeah. So, from the internal perspective, of course, a summary of your findings to include a summary of findings from any analytics or data review, I think is obviously very important. In terms of suggestions or recommendations at the end, I typically tend to find a gray area there where I can talk about some potential root cause issues, maybe hint at the controls weakness or culture issue. So, give them a starting point, but certainly short of a recommendation.

Matt: Okay. And Alejandra.

Alejandra: So, I think similar to what’s been said, and I think less and less clients are wanting full reports. You know, I think short PowerPoint presentations with oral discussions about findings and recommendations tends to be more common now. With respect to recommendations, certainly, where there are improvements based on a root cause analysis, improvements in the compliance program and controls would certainly make those recommendations. And there’s always, of course, discussions prior to, I agree with Gabriel putting final pen to paper. And with respect to, you know, HR and disciplinary decisions that it’s a more difficult call. But I have been in situations where I’ve made disciplinary recommendations again in alignment with a client, but in writing.

Matt: And then we only have about five minutes left. So, I also did want to set aside at least some questions just to about COVID-19 and how that has complicated investigations these days. I will just ask you all very quickly, what have you found to be the most challenged part of investigations, thanks to COVID-19, whether that is interviews or just the pace of investigations or whatever else that you find COVID has really transformed how you’re doing investigations. Gabriel, I’ll start with you and then Scott, and then Alejandra, like what is really jumped out at you over the last four or five months?

Gabriel: Well, the pace of document production has been affected by some of my recent investigations simply because representatives of the organization don’t have access to their workplace. That complicates things slightly. Obviously, there’s little or no in-person interviews, the interviews are typically taking place audio on the phone. That doesn’t terribly trouble me though. I’m still getting the basic information that I need moving forward. And going back to what I said earlier, you know, I’m fairly flexible in conducting these investigations and it doesn’t trouble me at all to have to do so with interviews that take place over the phone as opposed to in person. You know, I’m not going to get the body language effect, but I feel like that can be overcome in any case.

Matt: Okay. Scott, what’s your impressions these days?

Scott: You know, again, thinking of this, you know, webinar is focused on the human element, I again began with the empathy, people have changed jobs. A lot of them changed roles. Their workforce is perhaps smaller or there’s been a change in their relationship to work. And so, you know, getting people comfortable with more impersonal reporting and more impersonal interviews, whether that is somebody on staff or somebody in the C-suite, I think is key. And making sure that, you know, you meet folks on their turf. So, providing them with checklists, instructions of how to accomplish and be a good participant in a video interview as I think is where we’re headed there.

Matt: All right. Alejandra.

Alejandra: I would say, so the investigations that I’m working on right now is all been through Zoom. So, I’ve had access to employees more readily in some cases because no one’s traveling. So, they’re home. But it has, just from my experience in the last couple of weeks led to some challenges, particularly around privileged considerations, for example. So, we were in the middle of an interview with a witness, an employee, and just casually in the middle, like maybe an hour into the interview, she mentioned that her husband’s in the room. You know, even though we gave all the appropriate instructions at the beginning and confidentiality and, you know, you hit pause at that moment. And, of course, reminder her, right? “This has to be just us, please bring yourself or ask him to leave so that you can have the privacy and the confidentiality that’s required.”

I had another employee ask if she could record the conversation, which, you know, she asked, but we don’t know whether or not there was a device that’s recording the Zoom conversation. Screenshots, you know, we’ve had to show documents in this investigation and we’re projecting them on the screen. I don’t know if someone’s taking a picture or taking a screenshot of a document, who they’re sharing it with. I did see an interviewee look towards her left, which indicated to me she was reading something. you know, so then again, asked her what the document is. Is it something we had and requested that she send it to us, but those are new challenges that will, I think, continue as also clients realize you can conduct investigations remotely, even when things go back to normal, I think we’re going to see a lot more of what we’ve been living.

Matt: I have even heard of investigators testing angles of cameras and then asking investigation subjects to please use your camera angle this way so that we could see your hands or your table or your room. I know it is that nitpicky these days, but you are right. We are going to be doing this for quite some time yet. So, we are at the end of this hour, so we will have to close here. But, Alejandra Almonte and Scott LaVictor and Gabriel Imperato, thank you very much. This has been a great hour. And I know we have a lot of other questions we didn’t get to. I think if Compliance Line can send those out, we’ll try and answer them maybe by email or something. Nick, I’ll turn it back to you and Gio and you guys can wrap it up.

Giovanni: Yeah. Thanks so much, everyone for jumping in. If any of you can stay on let’s do cover, you know, just one or two of these questions, and attendees can choose to stay on and, you know, if you need to go to your next appointment or obviously any of the panelists, if you need to go, that’s fine. But this will be recorded and you’ll be able to see it as we cover those. Are few of you panelists okay staying out for that?

Scott: Sure.

Alejandra: I can stay on for a few minutes. Yeah.

Gabriel: A few minutes. Yeah.

Giovanni: Nick, do you have a bigger one you want to throw in?

Nick: Yeah. I’d like to talk a little bit about this attorney-client privilege and how you think about investigations into the context of those. So, should they be conducted under attorney-client privilege?

Gabriel: Well, I’m happy to respond to that initially. Usually, I’m called in to conduct an internal investigation of a fairly serious report of non-compliant activity. And, you know, I would strongly recommend under those circumstances that the investigation be conducted under attorney-client privilege. This isn’t a routine audit. This isn’t a monitoring function out of the compliance department. This is an internal investigation of a significant report of non-compliant activity that could have serious liability ramifications for the organization, especially if the information got into the wrong hands. So, I’m usually discussing the application of attorney-client privilege right away upfront, and then setting it up and documenting it accordingly and carefully, you know, for future reference.

Giovanni: Anybody else have anything to add to that? I think that that was pretty thorough, but please jump in.

Alejandra: Certainly agree. And I think that’s where that initial risk assessment scoping comes in at the beginning, right? Not necessarily every single investigation needs to benefit from attorney-client privilege, but that decision needs to be made very, very early on, or as soon as there’s a change in the investigation that might trigger the need for privilege.

Giovanni: Awesome. Thanks so much. So, I think that we talked a little bit about reinforcing your culture and your openness throughout this process and how the investigation that you run can really kind of carry over into how people perceive the culture at large or the compliance department. I’d love to talk about that a little bit in the context of what information you give back to the complainant or the initial reporting party. There’s obviously a wide range of those. So, I’d be happy to talk about kind of the exceptions or kind of how you set a standard around that. And how do you make them feel that it resulted in a complete investigation when obviously there are some things that you can’t or shouldn’t disclose. Do you mind getting us started, Alejandra?

Alejandra: That is the $10 million question, right? I think if we approach this from the premise that, you know, I was referring to earlier where you communicate quickly and you find different touchpoints throughout the investigation to communicate appropriately to the complainant, it becomes less of an issue at the end because they’ve gotten the sense that you’ve managed it appropriately, that you’ve been responsive, that you’ve been thorough. And, you know, one of the things, again, to humanize this is, at the end, just say, you know, we’ve taken appropriate measures and what you can share, you can share. And if the person continues to probe, just say, “Look, you know, we conduct these investigations through confidentiality for all parties involved. And just how, you know, obviously this, you would want your confidentiality protected, we have to extend the same courtesy, if you will, to the person who’s been accused.”

Giovanni: So, that sounds like great advice kind of messaging that throughout the investigation and giving them some broad sense of kind of where that line is. Gabe and Scott, do you have anything to add to that? I know that it’s something, we get questions about a lot, and everyone’s always trying to kind of balance, you know, transparency and confidentiality.

Gabriel: Well, I would just say that oftentimes in investigations, it becomes important to go back to the reporter and ask follow up questions. So, that serves a couple of different purposes all at once. But if that wasn’t the case and I thought that it was important to let the reporter know of progress in the investigation without disclosing attorney-client privileged information, there’s a number of ways that you can do that effectively without compromising your investigation.

Giovanni: Thanks, Gabe. Scott, were you going to jump in?

Scott: Yeah, I certainly agree. I think I’ve used all those techniques sometimes multiples in a single conversation, but letting folks know that they’ve been heard, that there’s a process that’s underway, that confidentiality means something and it has an impact on what you share with them and make it personal saying, I think as was said previously, you know, we strive to keep all the information confidential, including yours. And so, we can’t share too much. And the meaningful follow-up questions. I think this has come up a couple of times that ability to show progress, show investment, show concern for the report by asking meaningful follow-up questions is probably the most powerful tool we have.

Giovanni: Awesome. Well, we can wrap up with that. I appreciate all of you staying on for an extra few minutes. I’m just so excited that we could get this collective brainpower together on this panel and share this with our audience. It’s really been a blessing to everyone. So, thank you all for sharing your experience and your insights with us. For everyone who attended and they’re still on, thank you so much for spending some of your day with us. It’s been our pleasure to serve you this way and give you some of these tips so that you can help make your team better and help achieve your mission. We will be sending up a follow-up confirmation and information about SHRM credits as well as some other things so that you can access some of this content. So, thank you for joining us today. Thank you for, to Matt Kelly, thank you for hosting our Masterclass on Investigations. It’s been a real pleasure and people’s lives are going to be better for having this information. Thank you, everyone.

Matt: Thank you.

Gabriel: Thank you to everyone for allowing me to put this across. Take care.

Alejandra: Thank you very much. Yeah. Thank you for the opportunity.

Giovanni: All right. Everyone, stay safe out there.

Alejandra: You too.